Scott Finch

Scott Finch is an artist exploring an existential terrain in his paintings and comics. You can read my review of his new book here. This is an exciting time with the new book available in print as well as being serialized over at our friends at Solrad. In this interview, we discuss his latest book, a graphic novel, that is a mashup of end time fables and a satire on consumer culture. What immediately follows are some additional notes on this new book, The Domesticated Afterlife, proceeded by a transcript to our conversation. You can also view a video podcast of the interview.

Scott Finch is an artist engaged in the comics medium as an art form. It’s a distinction always worth making and exceptionally worthwhile in this case. Finch is a working artist in every sense. His MFA work was in Painting and Drawing. Over the years, he established a relationship with a local gallery, and he’s been producing work ever since. But it wasn’t until the age of 40 that he embarked upon working in comics. It is this fine art background that enriches his comics and helps make possible his ambitious and beguiling graphic novel, The Domesticated Afterlife.

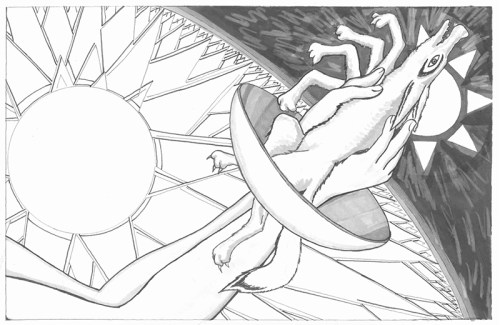

Any multi-layered book like this one will seem to challenge the reader at first, but its quirks are too enticing to resist. At once cerebral and as accessible as child’s play, the reader will revel in this world upon world of cats, dogs and chickens. The overriding conflict is a relentless search for meaning. The chickens seem to have the upper hand but it’s just as likely they merely sit atop a house of cards.

Part of the magic to this uncanny eschatological fable is the drawing. These animal characters are avatars linking back to childhood, to the beginning of time. Dog. Cat. Chicken. These are some of the first friends we make as children. They speak to us at a profound level before we can even speak ourselves. An artist like Finch is in tune with that sixth sense that summons forth the kind of primal visions you will find in this exceptional book.

From the start, it’s clear that this is going to be a story of mythic proportions: it all begins with a wolf tricked into becoming a cog in some alternate reality. For the price of freedom, the wolf has been enticed with security. In this metaverse, the wolf is now a dog-like humanoid enslaved by the perpetual cycle of monotonous work. There’s no end in sight with a blur for a present and a swipe of the past.

In this metaverse, former animals have lost touch with nature and are chained to the artificial. Having lost the thrill for life, these dead-enders are malleable to the extreme, prone to wasting away and becoming addicted to nothingness. But there’s always a glimmer of hope at large and some souls are just too stubborn to snuff out. Finch weaves a delicious cautionary tale. Of course, no animal, nor human, should give into becoming domesticated. Finch rides this theme for all it’s worth, punctuated by some of the most memorable images I’ve ever come across in comics. You too will be captivated by chickens in various states of ennui. Plenty of food for thought and it’s also just a lot of good old-fashioned loopy fun.

HENRY CHAMBERLAIN: What is The Domesticated Afterlife about? Is it fair to say that it’s a bit of mashup of end time fables and a satire of consumer culture? Is that a fair assessment?

SCOTT FINCH: I think that’s a really fair assessment. The story begins for the main characters in something that feels like the end times. And it’s something similar to the working culture that I experienced when I was a bit younger. You also have characters trying to be happy with what they can consume in this culture and not satisfied and wondering what can be done about it.

What can you tell us about how you work in comics? How do you structure your narrative?

I started out with an idea for a beginning and an end but not the middle. I had an idea of characters who represented different perspectives. One would be more sensory and tactile. One would be more intellectual. Another more spiritual. And then one that was more of a pragmatist. These would be different types, like in The Wizard of Oz. These characters needed to find each other, figure out how to work together, and find a solution to the problem they found themselves in together.

A Little World Cunningly was your first work in comics in 2013. What can you tell us about that?

This is also a sort of journey into an other world. Both of these stories are created worlds that, like any other world in fantasy or science fiction, is a comment not only on our own world but an interior journey. That story, from 2013, is more of a story about creativity and how things can go wrong. It starts with a character who is making a world but he starts to think that maybe he’s really the only thing in the universe. He makes his world according to his own vision and it’s a mess.

Your background is in drawing and painting, that’s what your MFA is in. And then you made the transition over into comics. What brought you to comics after having been a painter for such a long period of time?

I was always making figurative paintings that had an implied narrative or suggested themes beyond the static image. A reading of one of my paintings would hopefully suggest a wider world and an activity before and after. The paintings are best understood within a body of work, or an exhibit, instead of just a solitary painting. I like people to experience my paintings in groups in exhibits of ten or more images. The relationships between those images creates a movement or momentum. Still, it took me until I was pushing 40 to think I could make sequential images and have them relate to each other in time. I don’t think I’ve ever been a rational planner with art. I’m more led my imagery and ideas that force themselves on me. Then I get dragged into what I’m going to do next.

One day, I was just taking a long walk and all this Carl Jung, Joseph Campbell, early Christian Gnostic myth, Greek myth, all this Hellenistic stuff I’d been reading, for a dozen years or more, shaped themselves into that first book, A Little World Made Cunningly. I thought to myself, Yes, this story is here, I’ve read it a hundred times in different cultures, different ways told, but this is my way to say it. Not that it was just mine, my idea, but that it was just sort of there. So, I thought, I’d better write this down before I forget it, like waking up from a dream. And then I drew it as fast as I could, before I forgot it. And what I found was that all the parts were there but when I went to work on them, it wasn’t just one idea. That outline actually has another ten ideas under it. It came to me as sort of imagery; it was all just there. Something unconscious is chugging away in the background and pushing its way out into my sketchbooks, into my work. Eventually, I bumped into that. And then it made sense and I could see how all these things should follow one after another.

You had mentioned to me earlier that one of your instructors was Susan Moore, wife of master cartoonist Charles Burns.

Yes, Susan was my teacher when I was at Tyler School of Art. I knew who Charles Burns was. I’m squarely in Generation X. He was not a minor figure in the pantheon of that time. But I was so far away from thinking about comics. I was just thinking about making paintings. And I was thinking it was painting where you delved into art. I just had a small idea of what that meant at that time.

You followed up with a short work in comics, Form and Deed in 2014. What can you tell us about that?

Somewhere along the way, I realized that if I wanted to untangle the sore muscles and stress in my body and the worry that I needed to sit down every once in a while and be quiet. Once I had that idea, I made a practice of it. But before I could get to any kind of quiet, or stillness, when I closed my eyes there generally was just a lot of imagery there. Some of it would just be worries and thinking about the day. As that settled down, I still hadn’t reached quiet. It was replaced my sort of hypnagogic or dream images or symbolic images which I mostly never really understood at all. Or they’d be very specific images of being in a place unknown to me. And it was one of those series of images that’s in the book. At some point in that process, I did get to a kind of quiet place where things loosened up. I felt still and okay. When I came out of it, I did my best to record that. So, that little story of passing through, that visionary reverie, and settling down, is a smaller story so it’s a smaller book. I wanted to see if I could draw some it and so that’s what is in the book.

Then we jump to 2020, to the title, Cheer Charm Life. Now, this is something that invites the audience to participate in a very tangible way since they can peel off stickers and create their own art. What can you share with us about that?

Those were all collages that I made on self-adhesive paper. Just drawings using a marker, mostly Sharpie color markers. I’ve been making them and sticking them on things. I have a friend who has an artist community and I’d go over and start sticking them in places, like in the kitchen, or on a bag of coffee. And then I noticed that if you put these images on top of these commercially produced images, they popped a certain way. They seemed like they fit together. I tried them out on different things and I found that cereal boxes really employed that bright color and poppy design, meant to be scanned and interacted with playfully, especially children’s cereal boxes.

I made a whole series of cereal box work. Once people found out I was working with cereal boxes, I’d come home to find a stack of cereal boxes on my front stoop. The fun thing about is that’s this inexhaustible perpetual drawing machine. Everyone has there own way to doodle and that’s what those were for me. And then there was taking the images and composing on the boxes, the field of play. It was a fun thing to do. Then the idea came up of doing a book and including stickers so that somebody else could play with them too. Antenna is the publisher. At the time, I still owed them The Domesticated Afterlife. At first, I was going to switch with them and just turn in the sticker book but they wanted to do both books. This was around the time that the pandemic started and that ended up giving me more time to really focus on completing the graphic novel.

The art world can seem distant to some people but it’s really like any other community or industry and it has its own language and jargon. I think of a term like, “process,” and how that can throw off some folks who immediately think it’s pretentious but it’s certainly not.

The idea of “process” doesn’t have to be precious or this high art elitist thing. When I started the cereal box project, I also started a job in the field of public art. I help the state of Louisiana place public art around the state. So, when I’d get home, after thinking about big public art projects, I wanted to turn to something light, disposable, the complete opposite of what I was thinking about all day.

Now, we come to your most recent work, The Domesticated Afterlife, in 2021. Would you share with us more about your influences.

First is the work of Carl Jung which I just gobbled up. I started when I was around 19 and to say I’ve read all his works doesn’t sound completely accurate but I think it’s pretty close, some of it very obscure and heavy. What he does is take you through the history of Western culture with an emphasis on images and the meaning of symbols and images. He refers you to the alchemists and the kind of pictures that they made and stories they told. Going to the irrational and bringing things back like the underworld journeys of the Greeks or the Popol Vuh in South America. Going to another realm and wondering if you can bring anything back from there. And, if you did, would you know what it was? I also love pictures of cosmologies through the ages, like Dante’s cosmology. Or beautiful images from esoterist Robert Fludd.

In comics, I was really blown away by Alan Moore’s Promethea. I still needed to get used to the artwork that had more of a superhero style. The same thing with Grant Morrison’s The Invisibles. It shows how esoteric and magical ideas can enter into sequential work and not seem so ephemeral and heady. Daria Tessler’s Cult of the Ibis is another great book, along with Loop of the Sun. Around the time that A Little World Made Cunningly was coming out, I discovered the Gnostic comics by Jesse Moynihan called, Forming, which began as a webcomic and that he continues to this day. I was just blown away by how deep and widely knowledgeable he is about the things I’m interested in.

Why don’t you name your characters right away? For instance, we don’t know the name of the main character until halfway into the book. Was that intentional?

Names are held back a lot. I do that in real life too! Saying someone’s name is a form of intimacy. That instantly brings you closer. I wasn’t sure when I was comfortable doing that with some of these characters. People who read the book kept telling me that I needed to introduce the names early on. So, yeah, it was an intentional thing but maybe ill-advised on my part. In fact, I was advised against it!

Maybe it’s a way to get the reader to focus more?

Maybe so. At the same time, I was still getting used to these characters and learning how to draw them. I concluded that, if I wasn’t going to name a character right away, then I had better make sure that the character looks the same from frame to frame. For this book, I didn’t really have a full sense of a map for it. I would do bits of it and reach a dead end and wait. It would be months, maybe a year’s wait, through chunks of it. So, yeah, it took me a long time to write.

The book certainly has its straightforward paths. I think it’s like any other book in the sense that some take time to get into. It’s definitely a great book for the times we live in, when it seems like the veil of reality has been revealed. All your characters are having to suffer through their delusions.

Yeah, the dogs are on a broken down ship, just on the edge of things. They never get a footing in this society. The books begins and ends with that ship.

What else can you tell us about what you’ve learned about the differences between painting and creating comics?

I think what I’m learning is to take my time and tell my stories visually. Whatever I want to say, I want it to be, first and foremost, visual. I think, for the first book, I was so concerned with pushing the narrative. I want to make sure that I get the lay of the land: What’s the imagery and can I stop and describe it? Can there be pauses and moments for the reader to get their feet under them? If I’m going to get sort of complicated, then I need to make sure that I provide some visual cues. If there’s things that are under the hood, then we need to pause and investigate them. I try to do that more in this new book, pause, give context, provide some clarity.

I love the world of comics and the world of painting. These are two separate worlds and yet they share common ground. I love chatting about how the two worlds might mix. In general, I think you pick up your own tips and tricks. One of the best bits of advice I got was from a self-taught painter who advised to always step back from your work because you can’t see it all at once.

When I first started teaching, that was one of the major things that I tried to teach early drawing students: the need to step back. They would bear down on their drawings until their faces were right up against their work. You can’t see that but they’re so interested on the part they’re working on. Everything loses proportion and the placement gets distorted. You lose the relationship between all the parts, like lights and darks. So, yeah, you had a wise teacher.

His name is Steve Parker. And I’m sure he’s doing well in Texas. Once you find your region, it’s hard to leave as it informs you and your art.

Oh yeah.

So, what do you hope readers will take away from your book?

I really hope that they enjoy it. I was talking with a friend who has read about a quarter of it so far and he thought it was really dark. And my response was, sure, that’s the setup. I can understand that you might not expect things to be as dark at first. I want readers to just experience and enjoy the journey. The end is a little ambiguous but it also has something to do with art and creativity and placing an emphasis on people and relationships.

From The Great Gatsby to Game of Thrones, it’s all a journey. And that holds true for The Domesticated Afterlife. Once you start, you don’t want it to end,

I appreciate that.

Where do you see yourself going next?

I have no idea.

Good.

I never had any idea that I’d do this book until I did it. Every time I put together a new show of paintings or drawings, my gallery director will talk about it being a departure and ask how I got there. You know, I think the work can suggest what may come next. I don’t feel committed to any particular medium or way of making things. But I really do want to make another book and I have some ideas for that. So, that should be the next thing. And, if it’s anything like this one, it will take a long time.

It’s good to have your comics online as it helps to make an artist feel less isolated.

I’m really excited that Solrad is going to serialize the book. It’s good to be able to get feedback like your review which meant the world to me. I made this book outside of a community working in comics. I really didn’t get a lot of feedback over the years as I worked on it. This is a gratifying time to put it out into the world and find out that some of the things I’d hope would resonate with readers are getting across. I had no certainty about that at all. So, I’m really hoping that it finds an audience, finds some people who will enjoy it.

Thank you so much, Scott.

Thank you, Henry. I really appreciate it.

Pingback: Comics Grinder