Comics and Modernism: History, Form and Culture. Edited by Jonathon Najarian. Oxford: University of Mississippi, 2024. 326pp, $30.

Guest Review by Paul Buhle

We find in the introduction to this interesting volume an assertion bound to astonish twentieth-century critics and scholars of comic art. Not so long ago, the great majority of the books and also most of the best work came from the ranks of the non-professors, self-educated devotees (aka “fans”). Editor Najarian quotes Dan Hassler-Forest saying, “From the mid-2000s onward, comic studies has become one of the most prolific fields of inquiry across a variety of disciplines.” (p.7). Najarian adds on his own dime that “New Modernist Studies,” heavily represented in this anthology, has taken up the study of print cultures at all levels, notably at the most ephemeral. Comics, for instance. In recent English Department fashion, scholars have also become fascinated with fascination, that is, how literary and artistic giants from Picasso to Dorothy Parker seriously loved comics and loved comics seriously.

Comics and Modernism is, therefore, an intersectional study, at an intersection never perhaps explored this closely or this variously. If the American Dadaists and their short-lived little magazines defended their choice of the lowest rungs of popular culture (including urinals), this scholarly move offers a sort of chronological starting point for studies of the “dispersive” character of comic art. That is, how comic art circulated, newspapers and magazine illustrations to comic books and beyond. Thence we dive into theory heading off in various directions. Finally, with some parting words from distinguished scholar Hillary Chute, we come to what the editor calls “the relentless materiality” (p.11) of comics, the physical facts of their creation, existence and appeal.

From a distaff angle, one might complain that the picture-story so far outdates Modernism of any variety that the association of the two may possibly suggest the effort of the art academy to evade the current, in some respects pervasive, sense of stagnation. To attach today’s audience interests in various aspects of popular culture to academic or museum projects would, then, offer a way to salvage scholars, curators and institutions from the threat of irrelevance.

Krazy Kat and Ignatz in full swing.

But this is surely too harsh. Many journalists and reviewers who dive cheerfully into contemporary graphic novels regard Graphic Novels as having a certain if admittedly vague and undetermined cultural status. With the historians of the dance or poetry, we cannot quite help ourselves from looking back to most of human history, the pre-literate and tribal part, as a time of picture-drawing, albeit on cave walls and such. At least from the printed word forward, we find pictures, and this must mean something for the jump-start in popularity provided the comic art genre by 1890s newspapers.

Muybridge Horse in Motion.

Comics devotees may nevertheless find the scholarship in Comics and Modernism rather daunting. Much of the volume argues analytical points through prolific use of examples in particular comic examples. Some of the research here is fresh and persuasive, other parts seemingly overdone, if any detail can be overdone for the compulsively interested specialist. It is as useful, for instance, to bring in Muybridge and the photographic study of motion at the end of the nineteenth century, as it was, a half-century ago, for scholars of film to argue that the silent film may have been created as much through the informal study of paintings as of following popular theater. Comics of the 1890s were treading new zones of visuality. But knowing this only takes us so far.

How do we understand better, for instance, how the abstraction of comics from “real life,” as the funny pages of newspapers, caught (and kept) the attention of the masses? The prestigious avant-garde mid-century critic, Clement Greenberg, a youthful radical who became a wild, almost hysterical Cold Warrior and denouncer of “kitsch” as harmful popular culture, argued that comics could only be mass-produced matter for brain-fogged masses. The content of true art, by contrast,would increasingly become about nothing but…itself. As Glenn Willmot suggests, this degree of misunderstanding was anything but accidental or arbitrary. A century after the Dadaists, scholars are still trying to find Cubism in the casual reading of the funny pages, when it’s not actually hard to find. A handful of comic artists, the most thoughtful, knew exactly what they were doing in modern art terms, and by the 1910s-20s made comic jokes about Cubism for their mass audience. Comic art beloved of the masses, at least certain kinds, never lost that level of sophistication. And it always told stories.

George Herriman.

So much attention is directed in Comics and Modernism to Winsor McCay (Little Nemo) and George Herriman (Krazy Kat) that admiring discussions of the artists and their work seem terribly familiar. It was pretty much all said, long ago. We are in a different territory discovering, for instance, that famed literary modernist author Djuna Barnes, launching herself as a Brooklyn journalist who could also turn out drawings more in the nature of political cartoons or caricatures than comic strips (i.e., sequential panels), meanwhile becoming quite the Greenwich Village bohemian, decades before publishing Nightwood, rightly considered a classic lesbian novel.

Why, however, is the remarkble, admirable Djuna Barnes in a book about comics? The answer, here and elsewhere, must be that “comics” as a subject have migrated to anything that Modernism’s scholars consider visually interesting and somehow vernacular. Rhythm magazine, appearing in 1911 in London, definitely blurs the line between art and text, with a line drawing of a bare breast in its “Aims and Ideals” manifesto (pp.136-37) leading to, or at least preceding, experiments in comics that have some uncertain relation with avant-garde little magazines. The argument is interesting but not persuasive.

An effort to connect illustrations for magazine advertising with comic art in the middle of the twentieth century makes sense in career terms, because many comic book artists in particular looked to advertising as a potential career advancement (that they were Jewish and still locked out of many jobs added to the lure). But this is mostly a scholar exploring his own fascinations, in this case with “the feminine.” The effort to relate comic superhero art’s muscularity to Italian futurism seems more visually convincing. Modern industry, motion, speed, all wrapped up in patriotic righteousness, offers hints of fascism (but also of a certain gay aesthetic), in line with how nearly all of which modern superheroes have been drawn, for forever. Sexual variance may indeed be the outstanding or unique aesthetic that remains or has been most noticed, along with race, as real comic books reach their final print era.

The most curious essay for me, as a boyhood devotee and later, interviewer and biographer of Harvey Kurtzman, is Andei Moloiu’s effort to draw this genius of satirical art into the world of Roy Lichtenstein and Pop Art. At a memorable 1990 MOMA show, Art Spiegelman objected stridently to the use of mediocre comics, barely transformed, into gallery art, mediocrity thus rendered yet more mediocre. Noted critic Arthur Danto, struggling for analogy in 1981, sought to argue that pop art actually transformed banalities into a celebration of the ordinary.

Had Harvey Kurtzman’s famed exploration of comic forms in the pages of Mad Comics and later works, actually moved toward the same end?

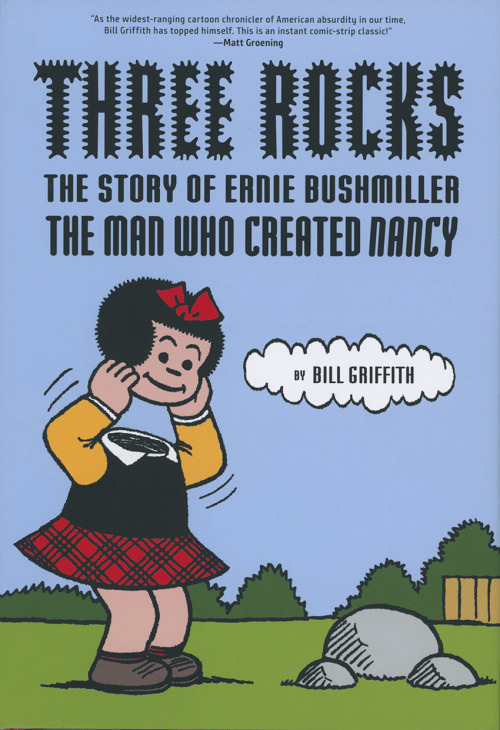

The argument can surely be made. One of 2023’s most important graphic novels, Three Rocks by Bill Griffith, explores “Nancy” artist Ernie Bushmiller’s own super-mundane life as a premier example of a career and a strip that cannot possibly be “about” anything but themselves. Here we may actually be back again, painfully for this critic, to what we might call the Cold War Art Thesis of the same Clement Greenberg. Social art, most especially including the public mural art of the New Deal’s Works Progress Administration but also the art of 1940s political radicalism and resistance, from the stage to films, had been thoroughly discredited and, what is surely worse, outdated. The end of (art) history had, for Greenberg, already taken place, much as the subsequent claim to the “End of Ideology,” Daniel Bell circa 1960 and Francis Fukuyama’s the “End of History” circa 1989, seemed to set sharp thematic limits on practically anything transformative that could happen afterward.

MAD #22, 1952.

But hold on. In satirizing 1950s American culture, Mad’s comic art was surely popular art turning in upon itself. The famed 1952 Mad issue, with the extended story of the modern artist described at length, was actually a satire upon the assumptions of abstract expressionism. Will Elder, the most dadaistically destructive (and favorite) of Mad writers and artists, went wild here. Mad and its editor, vivid enemies of Joe McCarthy and cultural/political represssion of the time, held more assumptions in common with the transformative impulses of the New Deal and the politics of the WPA artists than Greenberg could have imagined (or tolerated). The same Harvey Kurtzman, growing up in the Bronx with his mother reading the Daily Worker to him over the dinner table, was no Bolshevik, but cheerfully led a crew of creative talents with vividly antiwar “war comics,” including the current Korean War, and broke the racial barriers of comic art, just as the curtain fell upon the comics industry.

The penultimate essay looks at Art Spiegelman in light of Picasso, and this makes more sense in terms of Spiegelman’s artistic self-education and aspiration. Critic (and editor) Jonathan Najarian persuasively seeks to vindicate and to elevate Spiegelman to the level of the famed modern artists. But perhaps this admirable effort conveys the wrong aspiration. The most sophisticated comic art does not need to be placed alongside the masters of modern art. It has its own masters, or so many of us continue to believe.

Hillary Chute’s “Afterword: Graphic Modernisms,” sets us aright. She likes the phrase “the graphic” because it avoids so many dangers of reductionism. Not always. A local Wisconsin librarian and political progressive, learning about that new graphic novel, A People’s History of American Empire (2008), aka the Howard Zinn adaptation under my editorship, wondered aloud if anything “graphic” would be suitable for libraries to purchase. This problem has surely abated, in some respects, as the “GN” reached commecial success. Chute goes on to say that “comics is a medium that is formalist…aligned with modernist belief in the force of form—and also the irresolvability of form.” (pp.304-05). Comic art is indeed, or can be, both aesthetic and political to an extreme degree, caught up in the catastrophes of our times and even making sense of human possibility in an endangered, severely troubled world. In that last respect, comic art would be deeply true to the original intent of Dada, the great anarchic protest to the society that brought about the First World War—but hardly at all to Pop Art, for which marketing seems to have been the only purpose.