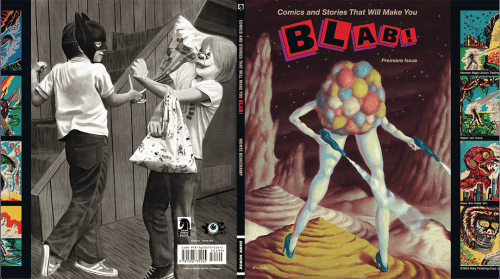

Cover: art by Ryan Heshka

BLAB! Editor: Monte Beauchamp, Dark Horse Books, pp 112, $19.99

Guest Review by Paul Buhle

BLAB!, a creation of the pleasingly twisted mind of Monte Beauchamp and his artists, has been around for quite some time. In fact, the first two issues (1986–87) were published by Beauchamp’s own imprint, Monte Comix. A genius at low-brow art anthologies, Beauchamp began this venture back in the transition or ditch between underground comix and alternative (what might later be called “art”) comics. But art, for Beauchamp, of an almost inexplicable kind.

The title has bounced from his own personal operation, Monte Comix, to Kitchen Sink Press to Fantagraphics and Last Gasp to Dark Horse, where it has become, for reasons known only to Beauchamp, “Blab World!” It was always a planet by itself, and the suspiciously camp rocket-firing goddess on the cover, by Hershka, is clearly interplanetary proof.

Excerpt from “The Death of Comics,” by Noah Van Sciver

Oh, yes, there is some truly understandable stuff here, a lot of it pages by Noah Van Sciver, at 38, the book’s youngest contributor. Louis Wain, a mad artist of cat images in Victorian Age Britain, could be a precursive Beauchamp, obsessed with images until he loses his mind. Van Sciver comes back again with a whopper, “The Death of Comics,” aka the story of the best-selling Crime Does Not Pay series. The genius money-making series created by leftwing publisher Ralph Gleason, it encompassed the noir sentiment of the later, disillusioned 1940s as the dreams of antifascist democracy melted into individualism and war-wounded minds that could not be healed.

Excerpt from “The Death of Comics,” by Noah Van Sciver

Van Sciver focuses in on the lives of the Crime Does Not Pay artists, and in particular the genius of graphic sex-and-sadism, Charles Biro. His triumph leads him and the rest of comics into the hands of would-be censors and especially best-selling author Dr. Frederick Wertham. It’s a familiar story to comics devotees, and involves a wider plot of horror comics, MAD’s publisher William M. Gaines, and Congressional hearings that mirrored the hearings held on the purported Communist threat,with near-identical warnings of dangerous Jews poisoning the minds of young Christians. Van Sciver allows himself only a glimpse of the larger picture, because he is following Biro to his own private doom.

Excerpt from “The Death of Comics,” by Noah Van Sciver

A considerable amount of the rest of BLAB! takes us to other strange places in the pulp past, comic book back pages of the 1940s-50s selling miracle hair-replacement liquids, pocket-size miniature monkeys, and other far-fetched hustles aimed at young (or low-capacity) minds. Or to the pulp treatments of great apes, “discovered” only in the mid-19th century, treated as fantastic King Kong types with their hands around near-nude (white) women, or as a link to the link of the “missing link” to the human race, a link that has never been found. Beauchamp is asking the unasked question, why the obsession, and answering not in prose but by throwing the question back at the reader. Another section offers pages and pages of 19th century attacks on Catholicism, the dangerous threat to everything truly American. Great flying saucer illustrations by Ryan Heshka take us back to the late 1940s and 1950s, the golden era of interplanetary visitations and expectations.

There’s more: Heshka and Beauchamp’s story on Superman’s inventors Siegel and Schuster, taken from Beauchamp’s own anthology Masterful Marks (on great comic artists) is wonderfully weird. He has created no iconic comic figures, neither prompted the empire of capital in comics or been cheated out of it, but he is so much a part of the history, one way or another, that one can hardly tell the larger story without him.

Paul Buhle’s latest comic is an adaptation of W.E.B. Du Bois’s classic Souls of Black Folk, by artist Paul Peart Smith (Rutgers University Press).